Aspiration and Integration: The Enduring Spirit of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh

HINDU NATION

MGR in the movie Idhaya Veenai song 'Kashmir beautiful Kashmir Kashmir wonderful Kashmir'. Shot in Kashmir.

The Unfolding Saga of Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir: A Historical Perspective

The year 1947 etched itself into the annals of South Asian history as the British Empire relinquished its hold, birthing the independent nations of India and Pakistan. Yet, this momentous occasion was tragically marred by widespread violence and displacement, a painful legacy that continues to cast a long shadow over the region. The hasty partitioning of the subcontinent triggered mass migrations and horrific communal strife, claiming an estimated million lives. The seeds of this tumultuous separation had been sown by the British policy of divide and rule, which had long exacerbated Hindu-Muslim tensions.

Amidst this upheaval, the 'Princely States of India', enjoying a degree of autonomy under British rule, were presented with the choice to accede to either India or Pakistan. Jammu and Kashmir, a strategically vital state bordering both nascent nations and characterized by a predominantly Muslim population ruled by a Hindu Maharaja, Hari Singh, emerged as a crucial point of contention. This very state became the crucible for the territories now known as Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (POK). This exploration delves into the historical trajectory of POK, tracing its origins from the chaotic aftermath of the 1947 partition and the ensuing conflict, through India's appeal to the United Nations, to the current political and administrative realities of the region, and finally, contemplating potential future scenarios that could influence this enduring dispute.

The Seeds of Division: Accession and Ambivalence

The formalization of the partition of British India into the independent dominions of India and Pakistan occurred with the Indian Independence Act of 1947. While the Radcliffe Line meticulously demarcated the boundaries of the two new nations based on religious majorities in British India, the rulers of the 562 Princely States were granted the autonomy to decide their allegiance, considering geographical proximity and the desires of their populace.

Jammu and Kashmir, sharing borders with both India and Pakistan, found itself in a uniquely precarious position. Maharaja Hari Singh initially harbored aspirations for his state to maintain an independent status. He reasoned that acceding to either dominion risked alienating significant portions of his population, with Muslims potentially dissenting from joining a Hindu-majority India and Hindus and Sikhs feeling vulnerable in a Muslim-majority Pakistan. In pursuit of his vision for independence, Maharaja Hari Singh proposed a Standstill Agreement to both India and Pakistan, intending to preserve existing arrangements concerning communication, trade, and travel. Pakistan readily accepted this agreement on August 14, 1947, while India sought further deliberations. However, Pakistan's subsequent actions would starkly contradict the spirit of this initial understanding.

The Invasion and the Instrument of Accession

The delicate balance was shattered in October 1947, a mere few weeks after the independence of both nations, when the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir was subjected to an invasion by tribal militias from Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province, allegedly supported by elements within the Pakistani army. This incursion, code-named "Operation Gulmarg" by the Pakistan Army, was aimed at forcibly seizing Kashmir and preempting the possibility of its ruler acceding to India. Driven by promises of plunder and religious fervor, the tribal forces unleashed a wave of violence, including killings, looting, arson, rape, and abduction, indiscriminately targeting both non-Muslims and Muslims in their path.

Faced with this existential threat and the inadequacy of his own forces to repel the invasion, Maharaja Hari Singh made an urgent plea to India for military assistance. India, however, conditioned its aid on the formal accession of Jammu and Kashmir to the Dominion of India. Consequently, Maharaja Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession on October 26, 1947, a document that was accepted by the Governor-General of India, Lord Mountbatten, on October 27, 1947. This legal act provided the basis for India's subsequent military intervention to defend the state against the invaders.

Following the accession, Indian troops were swiftly airlifted to Srinagar to defend the state. This marked the commencement of the First Indo-Pakistani War, a conflict that raged until a UN-mediated ceasefire came into effect on January 1, 1949. By the war's end, the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir stood divided along the ceasefire line, which would later evolve into the Line of Control (LoC). Approximately one-third of the territory, encompassing what is now known as Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, fell under the administrative control of Pakistan.

The United Nations Intervention: A Call for Plebiscite

In January 1948, India made the significant decision to bring the Kashmir issue before the United Nations Security Council. This move was driven by several factors. India perceived Pakistan's support for the tribal invaders as an act of aggression against its sovereign territory, especially following the legal accession of Jammu and Kashmir. Some accounts suggest that Lord Mountbatten, the Governor-General of India, advised Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to declare a ceasefire and approach the UN, believing that the newly formed international body would favor India's position and ensure Pakistan's withdrawal. Nehru himself reportedly held a strong belief in the moral and legal rectitude of India's stance on the Kashmir issue.

However, this decision has been a subject of ongoing debate, with critics arguing that it internationalized what could have remained a bilateral issue and potentially hindered a more decisive military outcome. Others contend that India, newly independent and grappling with numerous challenges, lacked the resources for a protracted war against Pakistan. Additionally, Nehru aimed to uphold India's secular ideals by ensuring the inclusion of a Muslim-majority region within the Indian Union.

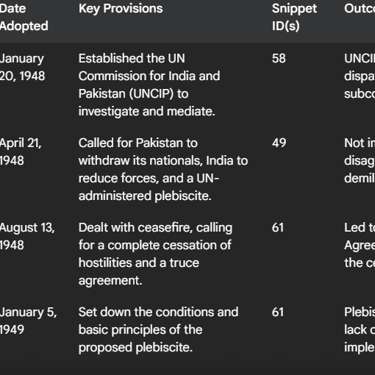

The UN Security Council responded to India's complaint by adopting several resolutions. Resolution 39, passed on January 20, 1948, established the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) to investigate the situation and mediate between the two nations. Subsequently, Resolution 47, adopted on April 21, 1948, addressed the core issue of resolving the Kashmir conflict. This resolution proposed a three-step process: first, Pakistan was to withdraw all its nationals who had entered Kashmir for fighting; second, India was to progressively reduce its forces to the minimum level required for law and order; and third, India was requested to appoint a plebiscite administrator nominated by the United Nations to conduct a free and impartial plebiscite to determine the future of the state.

However, both India and Pakistan harbored reservations about Resolution 47. India objected to being placed on an equal footing with Pakistan, viewing Pakistan as the aggressor and emphasizing the legal validity of the Maharaja's accession.

UNCIP undertook several visits to the Indian subcontinent between 1948 and 1949 in an attempt to facilitate a resolution acceptable to both India and Pakistan. The commission adopted resolutions on August 13, 1948, and January 5, 1949, which further elaborated on the ceasefire, a truce agreement involving the withdrawal of forces, and consultations regarding the plebiscite. These resolutions essentially amended and amplified the provisions of UNSC Resolution 47. Ultimately, UNCIP's efforts culminated in the Karachi Agreement in July 1949, which established the ceasefire line to be supervised by UN military observers.

Despite the call for a plebiscite in the UN resolutions, it has never been conducted. India considered the accession complete and viewed the plebiscite as merely a means of confirming the will of the people, while Pakistan insisted on the implementation of the UN resolutions and a free and fair plebiscite. The fundamental disagreement on the process of demilitarization, with India demanding Pakistan's withdrawal first and Pakistan seeking guarantees of India's subsequent withdrawal, resulted in a prolonged stalemate that continues to define the Kashmir dispute.The Current Landscape: Divided Administrations

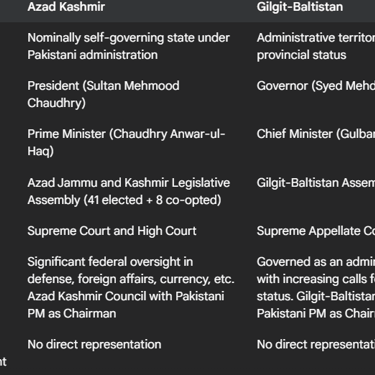

Presently, Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir is divided into two distinct administrative entities: Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan.

Azad Kashmir operates under a system of governance that is nominally self-governing, possessing its own president, prime minister, legislative assembly, and judiciary. The political structure adheres to a parliamentary system modeled after the British Westminster system. The Azad Jammu and Kashmir Council, chaired by the Prime Minister of Pakistan, serves as an oversight body for certain functions, indicating a degree of federal oversight. While Azad Kashmir has its own elected government, its relationship with Pakistan is characterized by significant federal influence, particularly in crucial areas such as defense, security, foreign affairs, and currency. Some observers argue that Azad Kashmir functions more as a local authority with limited autonomy, heavily reliant on and overseen by Pakistan. This has fueled discontent among some residents who feel that the region's resources are being exploited by the federal government without adequate returns. Recent years have witnessed political unrest in Azad Kashmir, with protests erupting over economic inequalities, governance shortcomings, and against perceived restrictions on political freedoms and independence movements. The government has responded by implementing measures to curb dissent and protests.

Gilgit-Baltistan, geographically much larger than Azad Kashmir, has a distinct historical background. Initially administered under Azad Kashmir after the 1949 ceasefire, control was later transferred directly to Pakistan. Currently, Gilgit-Baltistan holds a semi-provincial status within Pakistan. It has its own government, including a governor and a chief minister, and an elected legislative assembly. There has been a long-standing demand from the local population for Gilgit-Baltistan to be fully integrated into Pakistan as its fifth province. While the Pakistani government had previously resisted this due to its stance on the broader Kashmir dispute, in 2020, the then Prime Minister announced that Gilgit-Baltistan would be granted provisional provincial status. Despite this, the region still lacks full constitutional rights and representation in Pakistan's national parliament. Many residents desire closer integration with Pakistan, but there is also a sense of political ambiguity and disempowerment. Gilgit-Baltistan's strategic importance has grown significantly due to its location bordering Afghanistan and China and its role as a crucial gateway for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

On the Indian side of the Line of Control, the former state of Jammu and Kashmir has been reorganized into two Union Territories: Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh. Jammu and Kashmir continues to be a region marked by conflict and tension between India and Pakistan. An armed insurgency against Indian rule has persisted since 1989, with some seeking independence and others desiring to join Pakistan. India has consistently accused Pakistan of supporting these militants, a charge Pakistan denies. In a significant move in August 2019, India revoked the semi-autonomous status of Jammu and Kashmir by modifying Article 370 of its constitution, aiming for greater integration of the region. Recent militant attacks have further escalated tensions, leading to exchanges of fire across the border and diplomatic repercussions. A substantial military and paramilitary presence remains in Jammu and Kashmir.

Ladakh, separated from Jammu and Kashmir in 2019, shares borders with China and has experienced its own set of geopolitical tensions, particularly along the Line of Actual Control (LAC). While generally considered safe for travel, especially after a recent ceasefire in May 2025, the region has seen increased military patrols and restrictions on civilian movement in border areas following clashes with Chinese forces in 2020. Local communities in Ladakh have also voiced concerns about autonomy, the preservation of their unique identity, and the impact of development and border security measures.

The Line of Control (LoC) remains the de facto border between the Indian and Pakistani-administered parts of Kashmir. The United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) was established to monitor the ceasefire along this line. However, India has maintained that UNMOGIP's mandate has lapsed since the Simla Agreement of 1972, which stipulated bilateral resolution of disputes, while Pakistan holds a different view. UNMOGIP continues to operate, albeit with limitations on the Indian side of the LoC.

An Enduring Stalemate: Uncertain Futures

The issue of Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir remains a complex and deeply entrenched dispute with no easy resolution in sight. The enduring stalemate is evident in the lack of a mutually agreed-upon settlement despite decades of diplomatic efforts and UN involvement. Future trajectories for POK are uncertain and depend on a multitude of factors, including the internal political dynamics within Pakistan, the evolving relationship between India and Pakistan, and the role of regional and international players. China's growing influence in the region, particularly through CPEC, and the strategic interests of the United States in South Asia are likely to play a significant role in shaping future developments. The Kashmir issue remains a major impediment to the normalization of relations between India and Pakistan and continues to be a potential flashpoint that could destabilize the entire South Asian region

In conclusion, the takeover of the territories now known as Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir began in the aftermath of the 1947 partition of British India, fueled by the tribal invasion of Kashmir and the subsequent First Indo-Pakistani War. India's decision to approach the United Nations led to resolutions calling for a plebiscite, which has never been implemented, solidifying a territorial division along the Line of Control. Today, POK comprises Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, both under Pakistan's administration with varying degrees of autonomy and distinct political aspirations. The Indian-administered territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh continue to face their own political and security challenges. The Kashmir dispute, including the status of POK, remains unresolved, with the potential to impact regional stability for years to come.